Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the Earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists including EFree Associate Director Timothy Strobel and EFree Research Scientist Duck Young Kim has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being considered for next-generation, high-efficiency applications such as light-emitting diodes, higher-performance transistors and certain photovoltaic devices.

Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the Earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists including EFree Associate Director Timothy Strobel and EFree Research Scientist Duck Young Kim has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being considered for next-generation, high-efficiency applications such as light-emitting diodes, higher-performance transistors and certain photovoltaic devices.

Metallic substances conduct electrical current easily, whereas insulating (non-metallic) materials conduct no current at all. Semiconducting materials exhibit mid-range electrical conductivity. When semiconducting materials are subjected to an input of a specific energy, bound electrons can move to higher-energy, conducting states. The specific energy required to make this jump to the conducting state is defined as the “band gap.” While direct band gap materials can effectively absorb and emit light, indirect band gap materials, like diamond-structured silicon, cannot.

In order for silicon to be more attractive for use in new technology, its indirect band gap needs to be altered. The team was able to synthesize a new form of silicon with a quasi-direct band gap that falls within the desired range for solar absorption, something that has never before been achieved.

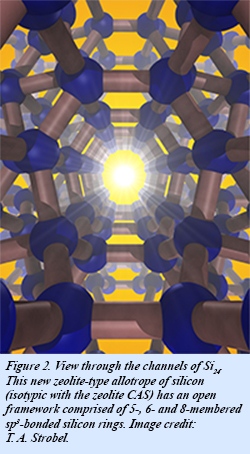

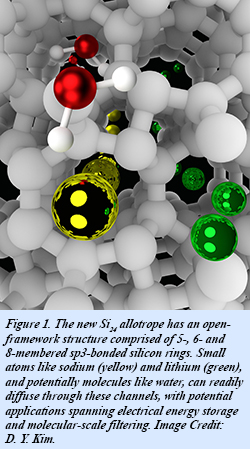

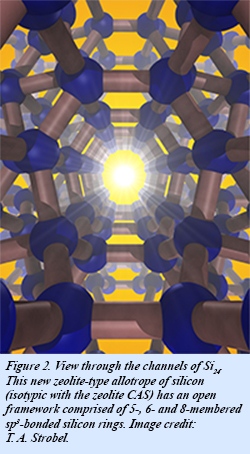

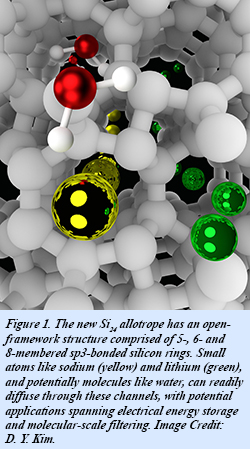

The silicon they created is a so-called allotrope, which means a different physical form of the same element, in the same way that diamonds and graphite are both forms of carbon. Unlike the conventional diamond structure, this new allotrope consists of an interesting open framework, called a zeolite-type structure, which is comprised of channels with five-, six-and eight-membered silicon rings. They created it using a novel high-pressure precursor process.

First, a compound of silicon and sodium, Na4Si24, was formed under high-pressure conditions. Next, this compound was recovered to ambient pressure, and the sodium was completely removed by heating under vacuum. The resulting pure silicon allotrope, Si24, has the ideal band gap for solar energy conversion technology, and can absorb, and potentially emit, light far more effectively than conventional diamond-structured silicon. Si24 is stable at ambient pressure to at least 842 degrees Fahrenheit (450 degrees Celsius).

High-pressure precursor synthesis represents an entirely new frontier in novel energy materials. Using the unique tool of high pressure, scientists can access novel structures with real potential to solve standing materials challenges. The Carnegie group demonstrated previously unknown properties for silicon, but their methodology is readily extendible to entirely different classes of materials. These new structures remain stable at atmospheric pressure, so larger-volume scaling strategies may be entirely possible [D. Y. Kim et al., Nature Mater. 14, 169-173 (2015)].

This paper was featured as a

highlight story on the website of the Advanced Photon Source.

Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the Earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists including EFree Associate Director Timothy Strobel and EFree Research Scientist Duck Young Kim has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being considered for next-generation, high-efficiency applications such as light-emitting diodes, higher-performance transistors and certain photovoltaic devices.

Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the Earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists including EFree Associate Director Timothy Strobel and EFree Research Scientist Duck Young Kim has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being considered for next-generation, high-efficiency applications such as light-emitting diodes, higher-performance transistors and certain photovoltaic devices.